26 Nov What do the ACC Sports probe, the NBN and Big Data have in common?

Posted at 00:00h

in Government, Growing Companies, Health & Community Services, ICT + DIGITAL STRATEGY, Local Government, Uncategorised, Utilities

Know more of our DIGITAL & ICT STRATEGY capabilities.

Each of these topics: The ACC (Australian Crime Commission) Organised Crime and Drugs in Sport investigation, the NBN (National Broadband Network), and Big Data are all very topical right now. So what do they have in common? I argue that they each relate to one of the latest emerging challenges associated with technology.

In Australia, the NBN is argued about every day, what technology at what cost and various options around how to do it better. While most agree on the benefit, most arguments surround the cost and the approach being taken. Just last week there were claims and counter claims about using Cable TV Coax as a stepping stone to a faster broadband rollout. Albeit not as fast as fibre but quite possibly existing infrastructure that could be put to better use than it currently is. Of course Telstra do use the Foxtel cable to provide cable internet to some degree. In considering the best option to improve internet speed quickly across Australia, accurate data on the existing infrastructure is important. But what happens if that data is wrong?

Well it is wrong. How wrong I don’t know but completely wrong in some cases. I recently moved home. The new apartment block I moved into was ADSL only…no cable, ADSL over copper phone line. On moving in, I plugged the usual array of cables in and Foxtel worked straight out of the wall…great! Made we wonder what the Foxtel guy was going to do when he turned up. He did show, and berated me for choosing ADSL over cable. “I didn’t request ADSL” I said, “Telstra says that’s all the building has got”. Well this bloke persisted, and I half paid attention, until he said “Give that a go”, pointing to my recently retired cable modem that he had plugged in. He was right, Telstra was wrong, I had internet via cable!

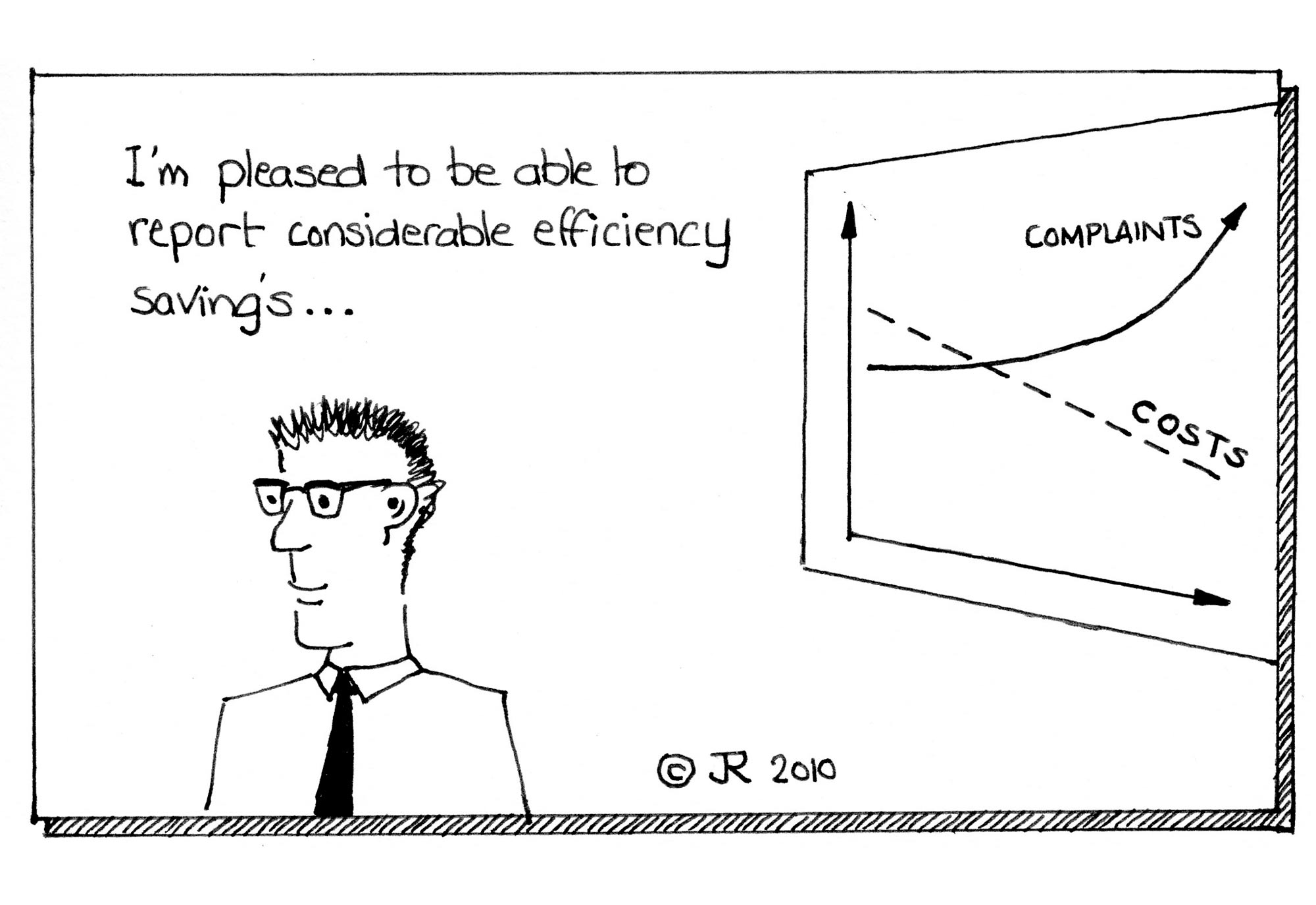

So how wrong are the records on what IT infrastructure exists in Australia? Anyone who has developed business cases and considered investment scenarios know that you can change any decision with a few tweaks of input data. What impact could that have on sound investment choices, particularly a $40B investment choice? But in some respects, errors of this type in corporate data is quite normal. So this should be expected and should (hopefully) have been catered for in every Business Case.

But this use of data is a rather conventional one. Big Data concepts take another step. With Big Data, there is the promise that with increased data we can gain more information, more insights, make better decisions, see things that we could never see before, or if we could see them, we can now prove them as fact. It can allow us to move beyond big monolithic data use, such as an investment case, and look at finer trends that we can apply to individual circumstance.

Big Data problem solving allows us to make decisions with more precision based on individual circumstances. This more granular decision making can define how we treat certain customer groups, certain profiles of people, pulling apart the broader community and understanding the parts that make up one.

It could be used for instance to move beyond an Australia wide internet business case and look at internet use and needs by geographies, by profession, by family type and many more criteria. Services can then be targeted more specifically to specific granular groups. The more detailed the definition of the group, the more potential for more personalised services specific to each of our particular needs. We could understand behaviours by a suburb, by a street, or an apartment block, or perhaps a family group.

The challenge when we get to this level of granularity is that error rates can skyrocket. For instance, if there is a 5% error rate in the data stored about cable TV infrastructure in Australia, then for that 5%, the data is 100% wrong. Let’s take my new apartment building. Telstra’s records aren’t 5% wrong here, they are 100% wrong. So if a marketer or a service provider or a government department was making decisions about people here based on that data they would be completely wrong. If they told the world about that then they would misrepresent us.

So in theory, while Big Data concepts sound full of promise, small error rates on a big population group, can turn into huge error rates on a small population group. So the quality of data and the assumptions and definitions about that data start mattering a whole lot more.

If the granularity of the data starts approaching very small groups, perhaps even groups of one, then at some point we stop being a statistic on customer behaviour and start becoming tracked, personally. In this case, those using that data are no longer doing statistical analysis, they are starting to do personal analysis.

If you stop to consider the type of data that is easily collected about you, then a picture can easily be built about you based merely on:

1. Topics of interest and personal/professional relationships

(from Phone calls and emails and other electronic communications)

2. Financial situation and financial relationships

(Banking and Financial transactions)

3. Where you have been and who you have visited

(Location based tracking from smart phones)

(Location based tracking from smart phones)

Information gathered by a bank and a telecommunications company could easily be combined to create a picture of you based on the above. So where should this line lie between you as a statistic and you being revealed and tracked as a person? What rules should therefore apply to that data as it approaches the level of detail that says something about you? This is an area of interest to policy makers, legislators and privacy advocates and understandably so. Information at this level of granularity would need to have some obligations and responsibilities that go with it.

Data gathering and analysis at this level has typically been the province of intelligence gathering organisations. They are regulated and trained in the appropriate use of such intelligence. The recent Australian Crime Commission announcements have upset some that feel they have been unfairly smeared as guilty when they are not. This has created debate about the way information of this nature should be managed and released. But these issues and the risks associated with them are moving beyond the specialised and highly regulated world of intelligence organisations and law enforcement.

Big Data concepts will allow analysis by organisations (or groups of organisations) to approach analysis of a group of one. And it is not currently governed by the type of control that the ACC operates under. And as my experience of Telstra data shows, in some cases they can have the most basic of data very very wrong.

Some people don’t care about privacy, they have nothing to hide they say and they stand for the greater good theory. But what happens if the data held about you is wrong. And what happens if that becomes public, or worse still, conclusions are made about you based on that flawed data. How do you defend that, and perhaps why should you have to?

With Big Data techniques, poor data integrity, lack of control and a lack of foresight by regulators about these emerging challenges, we may find that it is more than a few footballers and sports administrators facing reputation challenges in years to come.

It has been said that many technologies do not change human behaviour but accelerate or magnify the effects of it. False rumours have been in society for ever and a day. Will we now start facing false rumours, spread globally, and substantiated with specific facts…facts that are based on data that is fundamentally incorrect? Is anyone looking forward to a magnified future that looks like that?

Latest posts by Mark Nicholls (see all)

Share this post